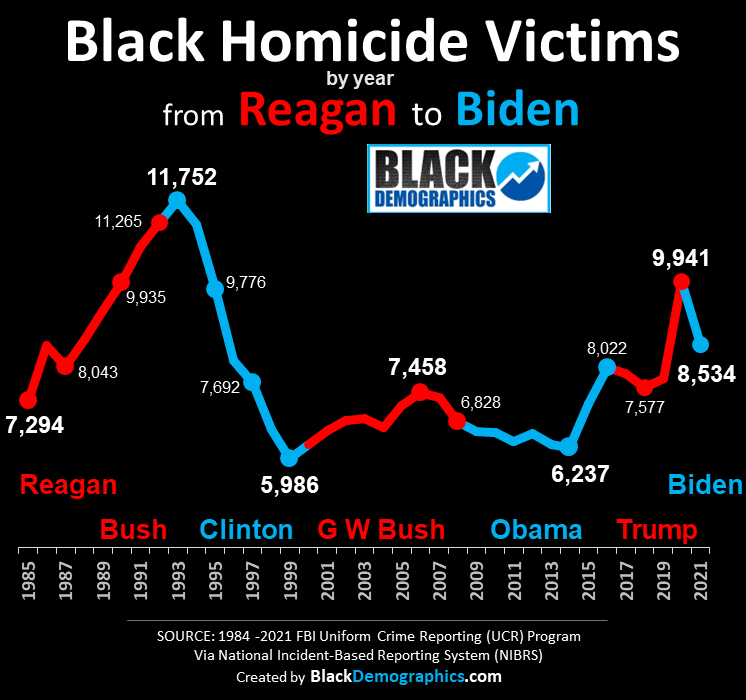

In the Reagan era, there was a significant surge in the volume of cocaine entering the United States. Once it reached the underground economy in American cities, it was transformed into a low-cost, highly addictive, smokable form. As this trend spread to major cities such as Los Angeles, New York, Detroit, and Atlanta, the profits generated from this trade were enormous, and it drastically altered life in neglected neighborhoods with high unemployment rates. Due to persistently high Black unemployment and a nearly 20 year stagnant Black/White wage gap since the 1970s, crack cocaine emerged as one of the primary employers in these communities among young Black men. However, the influx of money and competition also led to an increase in high-power firearms and violence.

Law enforcement agencies ramped up arrests through anti-gang task forces, creating power vacuums that were continuously filled by rival gangs and escalating violence. This resulted in a sharp increase in homicides, primarily involving Black men. Drug dealers began employing more minors, who were less susceptible to lengthy drug sentences, as arrests for drug-related crimes rose. This touched a larger cross-section of Black families living in these neighborhoods who were affected by drug addiction, addiction related crimes, drug dealing, incarceration, and drug related violence.

The FBI Uniform Crime Reporting program revealed that Black homicide victims reached an all-time high of 11,752 in 1993. However, as addictive drug use declined and law enforcement tactics intensified, the drug market’s profitability dwindled. By 1999, the number of African American homicide victims had dropped to 5,986—nearly half the figure in 1993.

This period also marked a time of national economic expansion, leading to decrease in Black unemployment and the growth of the Black middle class. A divergence emerged in the African American community between poverty and upward mobility, accompanied by Black flight from neighborhoods with high homicide rates and a narrowing of the Black/White wage gap for the first time in almost two decades.

As the nationwide economic expansion plateaued, annual homicides of African Americans saw a modest increase, peaking again at 7,458 in 2006 (still much lower than 1993) under the George W. Bush administration. The numbers then decreased to 6,237 in 2014 during the Obama administration. However, Black homicides spiked sharply by 2,200 in 2016 towards the end of the Obama administration and again by another 2,200 in 2020 during the Trump administration amid the pandemic.

At the time of this publishing the FBI has yet to release it’s numbers for 2022, however preliminary reports expect another decrease of approximately 5.4% from 2021.